New Readers/Findings/Nigeria/bg

- Facebook Messenger

- BlackBerry Messenger

- imo

- Candy Crush Saga

- Candy Crush Soda Saga

- 360 Security Lite

| |

| Нигерия | |

| Население: | 182,2 милиона |

| Internet access rate: | 51.04% |

| Wikipedia monthly pageviews: | 36 милиона |

| Research areas: | Lagos, Epe, Benin City |

| Research dates: | 15 май 2016 |

Themes

- General information seeking

- Technology use

- Trust

- Език

- Networks of influence

- Език

- Wikipedia awareness

- Wikipedia use

In-depth findings

Patterns are behaviors we saw across multiple people we talked to with shared characteristics. The patterns we saw aligned along 6 higher level themes. Some findings were observed in several locations, others are specific to one location.

Theme: Information seeking

Finding: People seek news and actionable information first, and context second.

In their day-to-day lives, people actively seek information to stay abreast of current affairs or to help them with immediate tasks. By and large, searching for reference information—including the type Wikipedia excels at—is a byproduct of news- or task-oriented information-seeking. That is, people look for reference information to help them contextualize current affairs or work on immediate tasks, and not as ends in themselves.

Patterns:

- (India and Nigeria) Event-based reporting travels better, both through i) analog, human networks, and ii) the digital social networks through which more and more people are now getting information.

- (India and Nigeria) People are task-oriented, rather than exploration-oriented, when seeking information. Most of the time, they want information to help them determine how to act, rather than context to help them evolve how they think.

- (India and Nigeria) Descriptive, contextual information requires further processing to become useful for decisionmaking. Doing so requires additional resources, both mental and potentially financial—the latter in environments where internet access is expensive and/or pay-for-bandwidth.

Finding: There is no one-stop shop for news and information.

People seek variety in their news and information sources. They recognize the comparative advantage of different outlets, and seek out Non local and local sources.

Wikipedia’s comparative advantage may come from both leveraging the perceived quality conferred to international sources, and increasing the local relevance and utility of its content. In specific markets, for example, Wikipedia could expand its content on national, historical drivers of crime to help readers interpret hyperlocal, weekly updates on crime hotspots.

Patterns:

- (India and Nigeria) People seek local (community or municipal) sources for timely, granular reporting on hyperlocal issues (e.g. weekly crime hotspots). These sources are seen as more useful for people’s day-to-day lives.

Finding: Only in specific scenarios do people scrutinize the credibility of an international information source.

- (India and Nigeria) For international information sources, people seem to only assess their credibility when the information will be used to complete tasks (e.g. for school, work) that will be assessed by an external authority. In these cases, most people attribute trustworthiness based on affiliation with widely recognized, ‘household-name’ institutions that are perceived to be reputable. These are typically those from media (e.g. Al Jazeera), academia (e.g. MIT), or non-governmental organizations (e.g. UNICEF).

Finding: People don’t need to trust an information source to find it useful.

People mostly seek information that is useful for some immediate purpose; ideally, it is from a credible source, but the source doesn’t have to be trusted for the information to be useful.

People are sophisticated in addressing gaps in the perceived utility or credibility of information.

Patterns:

- (India and Nigeria) If they find information that doesn’t meet their exact needs, they canvass and blend multiple sources—from personal human networks, offline sources (e.g. textbooks, newspapers), and digital channels—to answer their specific query.

- (India and Nigeria) If they find information of dubious credibility, they either discard it—especially in settings where search costs are relatively low (e.g. online)—or they try to validate it by comparing multiple sources.

Finding: Successful information systems meet users where they are today, while also evolving with their changing information habits.

As people experiment with new, digital information sources, human and analog sources remain reliable standbys.

Patterns:

- (Nigeria) Information ecosystems are all sociotechnical to some degree, but an end-user’s preferred ratio of human vs technological sources differs widely. Preferences are informed by one’s economic status, geographic location, personal networks, and individual characteristics.

Finding: Successful information systems meet users where they are today, while also evolving with their changing information habits.

Many popular information systems succeed because they let users choose how they would like to receive information, and accommodate changing information habits.

Patterns:

- (Nigeria) Nigeria’s lotto system, for example, provides many options for users to play and to get updates, including going to streetside kiosks, calling a trusted vendor, and getting updates on Facebook. This allows users to “grow with” the lotto as their own comfort level with new technologies expands, but doesn’t force them to learn new channels for the sake of that specific product.

Theme: Accessing the internet

Finding: Constant, individual internet access is not the norm for all.

Patterns:

- (India and Nigeria) Sharing devices with family members and friends is common among two key demographics: i) youth, and ii) people with low internet access.

- (India and Nigeria) Those borrowing devices do not see shared access as an inconvenience, but simply as a way to get what they need right when they need it.

Finding: Mobile dominates for getting online, and Android is the platform of choice.

Patterns:

- (India and Nigeria) Feature phones and lower-grade Android smartphones are the primary devices for connecting to the internet, widely popular across all user groups. Series 40, Symbian, and others are used, but to a lesser degree. Only the wealthy use high-end (e.g. Samsung) Androids, iOS, or BlackBerry, and, even then, most prefer their Androids as the primary browsing/tethering devices due to their cost and battery life.

- (India and Nigeria) Mobiles are preferred for light, day-to-day communication, whereas laptops and desktops are preferred for bandwidth-heavy communication (or memory-intensive applications) such as streaming or downloading video content.

Finding: In Nigeria, internet access has been prohibitively expensive. Consumers are savvy, price-sensitive shoppers with low brand loyalty.

- (Nigeria) 46% of Nigerians are online.[1] Historically, the cost of mobile data has been extremely high and a pain point felt by users across economic strata. In October 2015, the government deregulated data prices; since then, mobile data prices have been dropping sharply.

- (Nigeria) In this environment, users are highly price-sensitive and are opportunistic consumers of mobile data. Many have multiple SIMs and monitor service changes, special promotions, and bonus offers across mobile network operators (MNOs)—and frequently adjust their service plans to maximize their data use at minimal cost. MNOs, in turn, are constantly offering new promotions.

- (Nigeria) As a result of frustration with MNO price-gouging, mobile hotspots (e.g. MyFi devices) and cheaper data plans from new internet service providers (ISPs) are growing in popularity. Adoption remains contained to relatively wealthy, urban users since they require high upfront payments for hardware and subscription plans.

Theme: Understanding the internet

Finding: Mental models around the internet can be confused.

The term “internet” is not universally understood, even among those that are frequently using it.

Patterns:

- (Nigeria) People don’t always know if and when they are on “the internet”. For example, across all respondent segments, there was spotty understanding of how mobile apps work, and how they relate to the internet.

- (Nigeria) While people may not be able to describe “the internet”, they describe their practices of “browsing” and “using apps” based on how it impacts them economically. (This is unsurprising, given findings on the cost-burden of internet access.) The term “using data”, therefore, is a commonly used, universally understood substitute for “using the internet”.

Finding: People are learning how to use the internet from others, both loved ones and professional intermediaries.

Most people do not have a formal or knowledgeable source from which they can learn new technologies or the internet. Rather, such learning is typically social experience, happening through friends and families, and sometimes through niche retailers.

Patterns:

- (India and Nigeria) Digital immigrants are learning technology from digital natives. In particular, children are i) buying devices for their parents (mainly smartphones and tablets), ii) installing apps (mostly Skype, Whatsapp, and Facebook), and iii) teaching them how to use digital tools. This is especially common among young adults who are moving out, whose parents are especially motivated to learn new technologies in keep touch with them.

Theme: Using the internet

Finding: People are using the internet in English, without expecting otherwise.

While most people prefer speaking in local languages, these preferences do not seem to translate to reading or writing online. English is widely accepted as the lingua franca of the internet, even among those for whom English is not their mother tongue or a language of comfort. This is not perceived positively or negatively; rather, it is an unquestioned expectation of being online.

Patterns:

- (Nigeria) School instruction is in English or a mix of English and a local language. Literate people thus learn to read English first and have limited experience reading in their local language, which, when written, is typically transliterated in the Roman alphabet. As a result, there is no expectation of written content—online or otherwise—to be in local languages. The only popular media in local languages is oral (radio). English is therefore the default language of online activity, and Pidgin English is for interpersonal communications. When online, users may switch into local languages when casually communicating with close ones (e.g. via instant messenger), but the practice remains uncommon.

Finding: People are precious about data usage, and low-bandwidth browsers dominate.

Browsers designed for users with limited data bandwidth and/or inconsistent internet connections rule in both Nigeria and India.

Patterns:

- (Nigeria) In Nigeria, Opera Mini is popular because it helps “save on data”. Some users have a basic understanding of its built-in data compression features, allowing them to browse with less data, but do not understand its various data-savings modes. The ‘Opera Mini mode’ is advertised to extend a user’s data by up to 90%, something users do monitor via their data savings in-app dashboard.

- (India) In India, UC Browser has grown through word-of-mouth and is widely believed to be a faster browser. Interestingly, it does load web content faster through data compression (as with Opera Mini); but as data cost is less of a concern in India (compared to Nigeria), it was UC Browser’s gains in speed, and not its savings in data, that was cited as its unique selling point.

Finding: Mobile apps have exploded in popularity, with instant messaging and social media at the top.

WhatsApp and Facebook are widely recognized and used. Most mobile data users (even those with limited internet access) use at least one. A 2014 poll found approximately half of surveyed mobile users in both India and Nigeria used WhatsApp.[4] India is Facebook’s largest market globally, where it counts 16% of Indians (or 195 million people) as users. Nigeria is its largest market in Africa, where nearly 10% of the population uses it.[5]

These trends are reshaping not just how people socialize online, but how they seek and share information in all aspects of their lives. WhatsApp is used to chat or joke with friends, but also increasingly as a key information stream. Some university students in Nigeria have a WhatsApp study group for every class. Facebook is used to reconnect with friends and play games, but also increasingly as a key source of news.

MNOs’ packaging of these apps in reduced- or fixed-fee bundles—where users pay an upfront fee for a suite of popular apps, after which data usage is free—will only help their ballooning popularity.

Patterns:

- (Nigeria) Beyond messaging and social media, other popular apps include utilities and games. In 2015, the most popular apps included (in descending order of popularity)

Finding: Students and educators often have conflicting views on if and how the internet can support formal education.

Students are uninspired to learn from traditional academic materials, as they see the content as outdated and unengaging. As a result, they copy peer notes and memorize information to get through assignments with as little investment as possible. The internet motivates students to learn, but many educators restrict their ability to use it.

Patterns:

- (Nigeria) Educators’ own limitations and self-interest constrain students’ ability to experiment within, expand, and enrich their information ecosystems. Primary- and secondary-level teachers typically have limited internet literacy themselves, and tertiary-level teachers are incentivized to restrict online learning. Some university lecturers demand students buy their authored textbooks, so they can benefit from sales proceeds, and emphasize that all the information students need for their class is in that one textbook. This discourages online learning.

- Despite this, students’ desire to use the internet is trumping institutional restrictions. Workarounds include accessing the internet off-campus (e.g. in cyber cafes, through smartphones outside class) and using online information sources, including Wikipedia, but citing other, acceptable sources as references.

Theme: Getting information online

Finding: People trust online search (and Google in particular) to get them what they need.

People rely on Google for all of their online search needs. It is perceived as capable of answering any query. Instances of Google’s personification indicate just how popular and beloved it is... "Uncle Google" (India), "Saint Google" (Mexico), "My Big Boss Google" (India), "Google Maharaj" (India), "Google is the solution to the world" (?)

Finding: Search habits are largely basic. Users surface what they need through trial-and-error queries, or by looking for quality indicators in the results.

Appearing in the first page of results in a Google search is key to winning traffic. Although specific search and result-selection behaviors differed between Nigeria and India, users in both countries typically did not venture beyond the first page of search results for most queries.

Patterns:

- (Nigeria) Users conduct online search with the intent of finding the best-fit answer to a query within top results. They test and subsequently refine their search query if desired outputs do not appear in the first page of results. Additionally, users also rely heavily on Google auto-complete to support their searches, and scroll through various suggestions to find the best match for their query.

Finding: In an era of search-led, task-oriented browsing, there is little loyalty to specific web properties—unless they relate to personal passions.

People trust Google to curate the right content for them on case-by-case basis. Unless it is a well-known local media brand or personality, people typically do not pay attention to the domain or source of the content.

A webpage’s perceived relevance or quality comes more from being on the first page of Google results, than from the name or reputation of its source. For some users, the only exceptions to this norm are the most well-known international universities (e.g. Harvard, MIT). People only memorize the names of websites—and go directly to them, instead of via search—that relate to their personal interests (e.g. Goal.com for football fans, Cricbuzz.com for cricket fans, IEEE.org for electronics enthusiasts, and TED.com for those who enjoy TED talks).

In these environments, it is difficult for international content brands to build brand awareness, let alone brand affinity or loyalty.

Finding: People are increasingly getting information online, then consuming or sharing it offline.

Users are frequently moving what's online to offline for repeated viewing, printing, or sharing. These behaviors are growing along with the tools that make them possible.

Patterns:

- (Nigeria) "Sideloading" and music/video sharing are common practices among the digitally savvy, helping users save on data costs (especially when sharing large files) and making technology and media discovery more social. As a result, file-sharing apps (e.g. Xender) are very popular.

Theme: Using Wikipedia

Finding: As a brand, Wikipedia is not widely recognized or understood. People are Wikipedia readers without realizing it.

Brand: Few respondents recognized the Wikipedia visual brand (the name was more widely known), or could accurately describe what Wikipedia was.

Mission: Other than expert respondents, virtually no one seemed aware of Wikipedia’s mission or that the larger Wikimedia movement.

Content: Only a few respondents understood how content creation and editing worked. Most either had never considered the topic, or thought that editing was done by those paid or otherwise assigned to do so (e.g. Wikipedia staff or foreign students working on assignments).

Patterns:

- (India and Nigeria) Many casual Wikipedia readers had no knowledge that they had ever used the platform. As Wikipedia articles often feature in first-page search results, many people have used it without realizing it.

- (India and Nigeria) Students are the exception to the above (that many casual Wikipedia readers had no idea they had ever used the platform). Even students with limited to moderate internet access generally knew what Wikipedia was and how it could be useful for them.

Finding: People confuse Wikipedia with a search engine or social media platform. This can create unrealistic expectations of its functionality.

As the most widely known internet brands (e.g. Facebook, Twitter) are social media platforms or search engines (e.g. Google), many other international internet brands are also lumped in these two categories. Mislabeled brands include Skype, YouTube, and Wikipedia.

At times, this can lead to unrealistic expectations around Wikipedia’s features—for example, those that think it is a search engine believe it should have more robust search functionality. False expectations, in turn, lead to poor assessments of Wikipedia’s design or performance.

Finding: Wikipedia readers are generally task-oriented, not exploration-oriented. Wikipedia is seen as a utilitarian starting point that sometimes surfaces through search, and not a destination in itself.

Readers believe Wikipedia’s greatest value is providing strong overviews of any topic, particularly of people, places, or events. They land on Wikipedia articles when they are among top search results, and use them as a starting point for further learning.

- (Nigeria) Readers go to Wikipedia to understand the meaning or definition of unfamiliar terms. At times, this leads to perceptions of Wikipedia as a dictionary.

- (Nigeria) A common use-case is to settle “bar bets”– arguments with friends that require an immediate answer (e.g. the height of a famous footballer). Students use Wikipedia to complete school assignments. Professionals didn’t seem to use it for work.

- (Nigeria) Readers appreciate how Wikipedia is organized and how it is optimized for scannability. Most like the topic overviews and the ability to jump to specific subsections. No observed reader looked at article references.

Finding: Wikipedia’s content model can arouse suspicion. Despite this, there was no observed relationship between trust in and reading of Wikipedia.

Trust in Wikipedia is shaken when people find out anyone can edit pages, especially in Nigeria, where the media is captured by political and commercial interests, there is skepticism that contributors could be neutral, and that the content they produce could be unbiased. Interestingly, however, trust in and reading of Wikipedia are not highly correlated. Even when trust is low—e.g., when a person has been specifically told that Wikipedia is not credible—reading continues when people perceive the utility of content to be high.

- Note: In the select instances where researchers described how Wikipedia worked to respondents, they did so at the end of research activities. Explanations were brief, and focused on how Wikipedia worked; they did not elaborate on why its model has been successful. A carefully designed communications campaign may yield different reactions and assessments of Wikipedia’s trustworthiness.

-

Chris

-

Femi

-

Helen

Phone survey findings

-

Do you use the internet

-

Top reasons for using the internet

-

Awareness of Wikipedia

-

How respondents learned about Wikipedia

-

Reasons for using Wikipedia

-

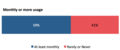

Frequency of use

-

Frequency of use

-

How interested were the infrequent / non-users

-

For those users with some interest, what was the biggest barrier

-

Smartphones vs Feature phone

-

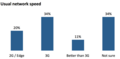

Mobile phone Internet access method

-

Mobile Network speed

-

Mobile Network speed

-

App usage

-

Gender

-

Age

-

Location

-

Geographical Zone

Methodology and participants

Field research in Nigeria and India was conducted using design research methods—that is, contextual inquiry using primarily ethnographic research methods.

Design research emphasizes immersive observation and in-depth, semi-structured interviews with target respondents to understand the behaviors and rituals of people interacting with each other, with products and services, and with their larger environments.

It stresses interacting with respondents in their natural settings and observing respondents in their day-to-day lives to understand their deeper needs, motivations, and constraints.

To understand underlying motivations and drivers, researchers probe for the why's and how's behind stated and observed behaviours.

Primary methods applied for this research

Ethnographic: Interviews

Semi-structured individual interviews lasting up to 1.5 hours. Conducted in context and in private—e.g., in respondents' homes, workplaces, or other natural locations—allowing researchers to observe and ask about artifacts in the environment that may give greater insight into respondents' experiences.

User Observations & Technology Demos

Guided observations of respondents as they live, work, and use different products or services to identify otherwise unarticulated needs, motivations, habits, and challenges that may be otherwise subconscious. Respondents "think out loud" (articulate their thoughts as they perform different tasks) to provide insight into their thought process and how they react to different environmental stimuli and/or design features.

Key Informant Interviews

Interviews with experts in various fields who have insights into market dynamics, user behavior, and other relevant topics for Wikimedia. Experts were largely drawn from the fields of technology, education, media, and telecommunications.

Participants

Staff involved

In Nigeria, three staff were in the field with Reboot participating in research. Abbey Ripstra, Lead Design Research Manager; Jack Rabah, Regional Manager, Strategic Partnerships – Middle East and Africa; and Zachary McCune, Global Audience Communications Manager.

Notes

- ↑ "Nigeria Internet Users". www.internetlivestats.com. Retrieved 2016-08-17.

- ↑ Widespread is defined as reaching 80% of citizens.

- ↑ Affordability is defined as a 500MB data plan that costs 5% or less of the average monthly income for 80% of citizens.

- ↑ Adika, Oscar (2014-03-05). "49% of Kenyan Mobile Users are on Whatsapp". Techweez. Retrieved 2016-08-17.

- ↑ Kazeem, Yomi. "More people use Facebook in Nigeria than anywhere else in Africa" (in en-US). Retrieved 2016-08-17.

- ↑ "The most popular apps on every Nigerian smartphone" (in en-US). 2015-11-06. Retrieved 2016-08-17.

- ↑ It was difficult to get specific figures for the most popular apps, and doing so was not a focus in this research. The ranked lists are provided as context only, based on analysis conducted by national media in Nigeria and India.