Wikimedia Deutschland/Movement Reporting/Software Development

| Overview | Volunteers | Software Development | Conditions for Free Knowledge | Wikimedia Movement | Finances |

*** This is Wikimedia Deutschland's 2018 midterm report to the Wikimedia Movement, covering the time period from January 1st - June 30th 2018. For the full-year report for 2018 please go to Wikimedia Deutschland Movement Report 2018. ***

Software Development: Expand Wikidata and Further Develop MediaWiki

edit

Our software development teams work on improving the software behind the Wikimedia projects and its usability. We constantly develop new solutions responding to user needs. Our work not only affects the various language versions of Wikipedia and Wikidata, but also actively supports Commons and other Wikimedia projects. Wikidata now has its own community and has grown into the data backbone of Wikimedia projects. Increasingly, it (and its underlying software, Wikibase) is used by knowledge communities and users outside of the Wikiverse. In 2018, our Wikidata team together with volunteer developers and editors from the Wikidata community worked on expanding Wikidata’s use and functionality for Wikimedia projects and also for partners from other spheres. In addition, we work closely with the developers at the Wikimedia Foundation and with volunteer FOSS developers to improve the MediaWiki software.

Goal 3: Increasing numbers of volunteers in the Wikimedia projects benefit from Wikidata. We promote the integration of Wikidata and other Wikimedia projects, and we create the conditions so that data quality in Wikidata can further improve.

|

During 2018 the Wikidata team has made significant progress towards making it possible to collect and edit data about words in Wikidata. This represents a major change, or rather, a substantial addition to the functionality of the knowledgebase: Since 2012, items in Wikidata (Q) had referred exclusively to concepts, and not to the word describing the concept. Since late May 2018, Wikidata is now able to store a new form of data: words and phrases in a multitude of languages. This data is stored in new types of entities, identified as Lexemes (L), Forms (F) and Senses (S). The structured description of the words will be directly connected to the concepts. It will allow editors to precisely describe all words in all languages, and will be reusable, just like the whole content of Wikidata, by multiple tools and queries. In the future users will be able to reuse lexicographical data on all Wikimedia projects, and Wikidata will provide support for Wiktionary. For more information, check the documentation page. Adding support for data about words is a major step towards opening up a crucial resource for language understanding, machine translation and much more especially for languages that are so far not supported because they do not have machine-readable dictionaries available to build tools upon.

Since the launch of the new entity types in June, over 40,000 new Lexemes in more than 100 languages have been entered by over 180 editors, and the numbers continue to grow. This is a great sign for an active community that formed around lexemes and been established now in Wikidata. The Wikidata team is continuing to collect feedback from the community and make improvements based on this feedback as well as building out the feature set. We are getting a lot of good and useful feedback as can be seen from all the excellent suggestions collected here. Two particular improvements stand out: (1) It is now possible to run queries for lexemes e.g. to find missing word forms or meanings, (2) senses are now part of lexicographical data, allowing people to describe, for each lexeme, the different meanings of the word which in turn will improve how existing lexemes are organized and inter-connected and provide a very important layer of information.

Some reactions on twitter:

-

Tweet about Lexemes by Erik Moeller

-

Esperanto LiberaScio responding to news about Lexemes

-

Tweet by John Samuel

Story: Lexicographical data on Wikidata: Words, words, words (by Jens Ohlig) |

| Language is what makes our world beautiful, diverse, and complicated. Wikidata is a multilingual project, serving the more than 300 languages of the Wikimedia projects. This multilinguality at the core of Wikidata means that right from the start, every Item about a piece of knowledge in the world and every property to describe that Item can have a label in one of the languages we support, making Wikidata a polyglot knowledge base that speaks your language. Expanding Wikidata to deal with languages is an exciting new application.

Lexicographical data means just that: data that can appear in a lexicon. What we’re dealing with here is the linguistic side of words. As the word “word” is already very loaded, we use the linguistic term Lexeme – a Lexeme is an entry in a dictionary. Lexemes are a little different from other entities in Wikidata and thus have a namespace of their own. Their entity numbers don’t start with a Q — they start with an L. At https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Lexeme:L1 you can find the first Lexeme in Wikidata, the Sumerian word for “mother”. As Sumerian is one of the oldest languages we know, and the word for mother is one of the most basic words in any language, this may very well be one of the earliest utterances in human history. Every Lexeme has Senses, which tell you what a word means in various languages. It also has Forms which describe how the Lexeme can change grammatically — just think of the 15 cases a noun can be used with in the Finnish language. Every Lexeme is for an entry in just one language. English “apple” and the French “pomme” are different Lexemes (L3257 and L15282). As Wikidata is a linked database, it can even link to an Item with a Q-ID that represents the concept of that Lexeme. You can learn more about the data model for Lexemes on the documentation page. Some Lexemes in some languages can take many Forms. To help you with entering them, there is help: Wikidata Lexeme Forms is a tool to create a Lexeme with a set of Forms, e. g. the declensions of a noun or the conjugations of a verb. If you want to add Senses (i.e. explanations what a word really means) to Lexemes, there is also a handy tool: Wikidata Senses shows the list of languages and number of Senses that are missing, then after selecting a language, shows a random Lexeme that needs a Sense so you can create it. Try it while waiting for your bus at a bus stop. It’s a quick way to contribute to Free Knowledge! Of course, you can also query lexicographical data. An interesting example is this query by Finn Årup Nielsen to query for persons with a surname that matches the past participle form of a Danish verb. Fortunately, there is a game that uses lexicographical data from Wikidata to help you with the memorizing: DerDieDas. Can you make it through 10 randomly selected German nouns with guessing the correct article? For those who already speak German, there is also a French version and a Danish version. As of March 2019, Wikidata has 43440 Lexemes in 315 different languages, dialects or scripts (14762 Lexemes in English, 10334 in French, 3039 in Swedish, 2651 in Nynorsk, 2095 in Polish, and 2027 in German — see the full list). While this is already a good start, it is clearly just the beginning. Start exploring lexicographical data on Wikidata and help build a new repository of Free Knowledge for language! [This article was first published on the WMDE blog on March 25, 2019 and has been slightly shortened for this report.]

|

Other accomplishments included:

- Constraint Checks: The improved Constraint Reports were activated for all logged-in users, in order to make erroneous statements more visible. We added additional types of constraint checks and a large percentage of constraint violations can be found using the query service. The continuous work here is increasing trust in the data quality of Wikidata. In order to strengthen this effect, we published a blog post explaining constraint checks and other useful tools for Wikipedians (see story below).

- Watchlist integration improvements: Earlier in the year, we improved how Wikipedia watchlists track changes in Wikidata. Complaints had been that watchlists included too much useless information on these changes. While the improvements were appreciated by community members and reduced watchlist entries substantially, there are still changes necessary, however these need to largely be made at the level of local templates.

- Wikimedia Commons preview: We added a preview of pictures that refer to Commons, in the form of a statement linking to files on Commons.

- Mobile term box: We developed a prototype of a mobile term box. This is a first step towards enabling editors to contribute more easily to Wikidata on mobile devices.

- Better suggestions: A new beta feature was released, improving the suggestions for entities. After enabling suggestions based on constraint value for the constraint section of a property a few months ago in August, we wanted to take these possibilities to a new level.

- Wikidata Train-the-Trainer: We ran our first pilot program for further training Wikidata trainers. We facilitated a total of three 3-day workshops in three different cities (Berlin, Cologne, Vienna) and trained a total of 18 people in possibly running Wikidata workshops.

- Wikidata birthday: In late October, Wikidata turned six years old! People and groups joined us in celebrating this amazing accomplishment by organizing many events in different cities around the world.

Story: Tools for Wikipedians: Keeping track of what’s going on on Wikidata from Wikipedia (by Jens Ohlig) |

If watchlists and recent changes are too much, there is also the Wikidata vandalism dashboard. You can use it to patrol Wikidata edits for all languages you know. Descriptions of items are shown in the Wikipedia mobile app, sometimes making it a target for vandals. Vandalism in this area may go unnoticed for a while and sometimes gets fixed by another reader which is suboptimal, to say the least. With the vandalism dashboard, we make sure that no problematic edit goes unnoticed for a long time. The Wikidata vandalism dashboard uses ORES, the service that uses machine learning for vandalism detection on Wikimedia projects. The dashboard allows you see unpatrolled edits related to a language in Wikidata and marks questionable edits. At a glance, you can see which recent edits may be vandalism and click through them quickly — of course, the final decision of what is vandalism should be made by a human, not an artificial intelligence. For smaller Wikipedias like Persian, going through the dashboard twice a day is actually enough.

To make sense of the what links from Wikidata to Wikipedia, it’s always a safe bet to look at the Page information of the Wikipedia article. It will tell you what Wikidata item relates to the article and what content from Wikidata are being used in that article — maybe in template, such as an infobox. This can be a lot, as the excerpt from the English Wikipedia page for South Pole Telescope shows. It also works in the opposite direction: Look up which Wikipedias use data from a given item by checking the Wikidata item’s Page information page

Monitor the changes you care about There are also several other little tools to make your life as a Wikipedian better. Let’s just have a quick look at them. The Wikidata SPARQL Recent Changes tool by Magnus Manske will give you diffs over time for items that match a SPARQL query, for instance all French painters in the first week of October 2017 with no bots edits included. There is always Listeria, also by Magnus — a much-used tool to generate lists from SPARQL queries on Wikidata to display on Wikipedia pages. You can use lists to monitor the items you are interested in and detect changes. Together, these are amazing tools for a wiki project to monitor all the changes to things that are important to them. Last, not least, there is the Wikidata Concepts Monitor, a sophisticated tool for data science that gives you a glimpse into the life of Wikidata.

Use the Tools! Wikidata gives Wikipedians many ways to track information and changes in a fine-grained way. Take some time to learn about the tools and make them part of your tool belt. After all, editing on Wikipedia is not much unlike good craftsmanship. [This article was first published on the WMDE blog on June 1, 2018 and has been slightly shortened for this report.] |

Goal 4: Wikidata and other open data projects increasingly benefit from each other. To this end, we make Wikidata and Wikibase easier to use for external projects, and we expand the opportunities for collaboration among the projects.

|

Wikibase is the open source software behind Wikidata. Therefore, Wikidata is an instance of Wikibase. Since Wikidata’s purpose is not hosting all data on everything in the whole world, we are encouraging scientists, groups and projects to install their own instances of Wikibase, enter their data, and make it available to the public. Through working with these groups and through talks and workshops with the partners that run their own installations, we are getting a better understanding of their capacities, needs, and barriers, and ways to improve the software.

In the first quarter, we went through a number of activities that make it easier for interested groups to install an instance of Wikibase for their data project. At WikidataCon in late 2017, we provided the first version of a Docker-based installation. This can be used to install Wikibase, including the query service, on one’s own server. In Q1, we further improved this Docker image. Over the following months, several workshops were conducted that gathered people and groups interested or involved in Wikibase installations, in planning new instances, in data entry and data presentation of queries. These events gathered people in Antwerpen, in Berlin, in New York, at the GLAM Wiki Conference, the CC Global Summit and at Europeana Tech.

-

Wikibase Workshop in Berlin, Germany.

-

Wikibase workshop in Antwerp, Belgium.

-

WMDE software developers at the Wikibase workshop in Antwerp.

-

Wikibase workshop in New York City, USA.

-

Wikibase Workshop at the GLAM conference in Tel Aviv.

A special project coming out of our collaboration with the German National Library is an assessment of using Wikibase for the Integrated Authority File (German: Gemeinsame Normdatei) which we are currently exploring with the German National Library. This collaboration presents a possible paradigm shift for national libraries: several libraries indicated a growing interest in Wikibase for their work during the GND Con in Frankfurt in late 2018 and are considering using Wikibase to enable Linked Open Data.

Despite these efforts, users report continous need for further improvements on the software and the installation process. Difficulties in the software include the integration of external tools such as QuickStatements or using the query service for new instances of Wikibase. We use this feedback to continue to develop Wikibase as a product. In case of the FactGrid project, the community of a Wikibase installation partner takes the lead and handles most of the challenges with some support from our team. A very active, motivated community is forming around Wikibase and this resulted in the founding of a new Wikibase Community User group, a new mailing list, social media groups, trainings and new videos and introductory materials for Wikibase.

The number of registered Wikibase installations correspondingly has risen to about 22 at the end of 2018, as documented in the Wikibase Installation Registry (itself a Wikibase installation). In addition, there are several other Wikibase instances and projects, such as FairData and parts of Gene Wiki Project, which are not included in this registry.

Overall, when developing Wikibase as a product, our focus lies on both Wikimedia communities as well as external users who would like to contribute to the ecosystem of Free Knowledge. Due to the institutions and communities expressing interest in Wikibase, Wikimedia Deutschland and the Wikimedia Foundation took part in a joint workshop in December 2018 for strategic development of Wikibase. The results of this consultation will be used to build an overarching strategy for 2019.

Story: Many Faces of Wikibase: Lingua Libre makes [ˈlæŋ̩ɡwɪdʒəz] audible (by Jens Ohlig) |

Languages and multilinguality have always been an important part of the Wikimedia projects. A project called “Lingua Libre” now aims to make languages and their sound freely available as structured metadata. WMDE’s Jens Ohlig spoke to Antoine Lamielle, Lead developer of Lingua Libre, about the project and its use of the Wikibase software. After all, Wikimedia projects are available in almost 300 languages. But most of these languages are accessible as a form of knowledge of their own only in their written form. Lingua Libre aims to change that by making the sound of a language and its pronunciation freely available in the form of structured data. Jens Ohlig interviewed Antoine Lamielle, main developer of Lingua Libre, about his project and how it uses Wikibase.

Antoine: I’m User:0x010C, aka Antoine Lamielle, Wikimedia volunteer since 2014. I started editing a bit by accident, convinced by the philosophy of global free knowledge sharing. Over time, I’ve become a sysop and checkuser on the French Wikipedia, regular Commonist, working on a lot of on-wiki technical stuff (maintaining and developing bots, gadgets, templates, modules). Now, I’m also the architect and main developer of Lingua Libre since mid-2017. Off wiki, I’m a French software engineer, fond of kayaking, photography and linguistics.

Antoine: Lingua Libre is a library of free audio pronunciation recordings that everyone can complete by giving a few words, some proverbs, a few sentences, and so on. These sounds will mainly enrich Wikimedia projects like Wikipedia or Wiktionary, but also help specialists in language studies in their research. It is a pretty new project, taking its roots in the French wikiproject “Languages of France”, whose goal is to promote and preserve endangered regional languages on the Wikimedia sites. We found at that time that only 3% of all Wiktionary entries had an audio recording. That’s really bad given that it’s a very important element! It allows anyone who does not understand the IPA notation — a large part of the world population — to know how to pronounce a word. From there, the first version of Lingua Libre was born, an online tool to record word lists. Nowadays, it has become a fully automated process that helps you record and upload pronunciations on Commons and reuse them on Wikidata and Wiktionary. We can do up to 1,200 word pronunciations per hour — this used to be more like 80 per hour with the manual process!

Antoine: The first version of Lingua Libre collected metadata for each audio record, but it was stored in a traditional relational database, with no way to re-use it. We wanted to enhance that sleeping metadata by allowing anyone to explore it freely. But we also wished to gain flexibility in easily adding new metadata. Wikibase, equipped with a SPARQL endpoint, offered us all these possibilities, and all that in a well-known environment for Wikimedians! Paired with other benefits of MediaWiki — version history to name only one — the choice was clear. In our Wikibase instance we store three different types of items: languages (including dialects) imported directly from Wikidata; speakers, containing linguistic information on each person performing a recording (what level he/she has in the languages he/she speaks, and where they learned them, accent etc.); and recordings. These are created transparently by the Lingua Libre recorder for each recording made, linking the file on Wikimedia Commons to metadata (language, transcription, date of the recording, to which Wikipedia article / entry of Wiktionary / Wikidata item it corresponds etc), but also to the item of its author.

Antoine: Using the same software as Wikidata has made it easy for us to build bridges with this project, and take advantage of this incredible wealth of structured data. For example, to allow our speakers to describe where they learned a language, we use Wikidata IDs directly. This has many advantages in our use; so when we ask a new user where they have learned a language, they have total freedom on the level of precision they want to indicate (country, region, city, even neighborhood or school if they wish to), most often with labels translated into their own language. Backstage we can thus mix and re-use the data of Wikidata and Lingua Libre via federated SPARQL queries (for example to search all the records made in a country, or to be able to listen to variations of pronunciation of the same word in several different regions) and all that without having to manage the cost, the limitations and the heavy maintenance of a geo name database! However, this is currently more of a set of hacks than a perfect solution. Wikidata items are currently stored as external identifiers in our Wikibase instance, and the entire UI / UX depends on client-side AJAX calls to the Wikidata API. The ideal would be to be able to federate several Wikibases, allowing them to share items natively between them.

|

Goal 5: Through sustainable development of the MediaWiki Software, based on community needs, we assure the increased usefulness of MediaWiki for the Wikimedia projects, jointly with the Wikimedia Foundation and the communities.

|

Our focus in development around MediaWiki is on solving user ‘problems’. As a result, we measure our impact in terms of how many problems have been ultimately solved through our work. This work begins with identifying and prioritizing the problem, then evolves into research/preparation phase, with development, testing and feedback loops, followed by more development, and then finally culminates in the rollout.

The Technical Wishes Project has been as successful as never before: several existing MediaWiki features were improved and important new features have been added. Feedback from the community as well as numbers of active users show the great usefulness of the new tools and features: the improved beta feature of Two Column Edit Conflict View has been activated by more than 80.000 users and received very well. The new Advanced Search extension has made it easier to conduct complex searches on all Wikimedia wikis and as of early April, a total of 496 wikis are using the the Advanced Search extension.

We continue to maintain close communication with the German-speaking and the international communities as well as with the Wikimedia Foundation. Among other things, we conducted feedback loops for the edit conflict feature, the ‘Book Referencing’ wish and the confirmation prompt for ‘Rollbacks’. At the Developer Summit 2018, we provided a presentation on “Growing the MediaWiki Technical Community” and prepared several development projects jointly with the WMF teams. During the second half of 2018, a team of volunteer developers also rolled out a new version of the RevisionSlider with our support in August and September.

In 2018, these features from the Technical Wishlist were rolled out internationally:

- ‘AdvancedSearch’ was rolled out as a beta version on all wikis in May. During the first month after roll out, it was activated more than 10.000 times. It was used to conduct 1664 searches in one week in late June alone.

- ‘Show text changes when moving paragraphs’ was rolled out on most wikis, and we almost completed the work on the backend of the mobile version.

- ‘Correctly move files to Commons (Fileimporter/Fileexporter)’ was activated as a small beta version on the de-, fa- and ar-Wikis.

- ‘Footnote Highlighting’ was rolled out on all wikis in November.

An overview of all projects currently worked on can be found on this page: WMDE Technical Wishes. The Technical Wishes team also published its lessons learned from the past 5 years of working on this project in the White Paper ‘Building tools for diverse users’. As written in the White Paper:

“Even though it all started with a survey, the Technical Wishes project always has been more than just that: It’s an approach to collect and prioritize technical needs in a collaborative way and to support diverse groups of users with technology. In this sense, the core feature of Technical Wishes isn’t the survey, it’s the community-centered process we apply – and this means profound research, transparent and continuous communication, close collaboration with the communities, as well as iterations, constant improvement, learning from failures and, last but not least, finding sustainable, unhacky solutions.”

Story: Eureka! A new visual interface for specialized searches (by Johanna Strodt) |

| Have you tried the new search page on Wikipedia (and other Wikimedia wikis) yet? Now everyone can carry out specialized searches without specialized knowledge.

All of this requires no search expertise whatsoever. Here’s the difference between new and old:

This isn’t the only way the search page was improved—Wikimedia contributors may find the newly improved “namespace” search useful. Namespaces divide all pages of a wiki into different areas with different purposes. To give you a few examples, there are:

——— These changes, called Advanced Search, were developed by the Technical Wishes team at Wikimedia Deutschland (Germany), the independent Wikimedia chapter based in Berlin. They were supported by the Wikimedia Foundation’s Search Platform team, who works on how the general searching experience in the wikis can be improved.[1]

1. They were formerly named, and began this project, as the Foundation’s Discovery team.

[This article was first published on the WMF blog on December 13, 2018 and has been slightly shortened for this report.]

|

Story: Building tools for diverse users: Lessons learned from the Technical Wishes project (by Michael Schönitzer, Birgit Müller, Johanna Strodt und Lea Voget ) |

Since the first Technical Wishes survey in 2013, we’ve learned a lot about community-centered software development. In the past five years, we’ve continuously reflected on our methods, and we’ve iterated and improved them to find the best ways how we can build software for the Wikimedia projects. Among all that we’ve learned, these are our main lessons:

Hopefully, our insights, lessons learned, and observations, help others to better understand the challenges when developing software for collaborative projects, or to get some ideas to improve processes and methods. We also hope it helps contributors to see how important their voices are in the development process. We have already learned a lot from working on Technical Wishes, and we are sure we will continue to learn something new every single day. We’re excited to tackle our challenges and open questions in the years to come.

|

Our Objectives for this year

edit| Objective:

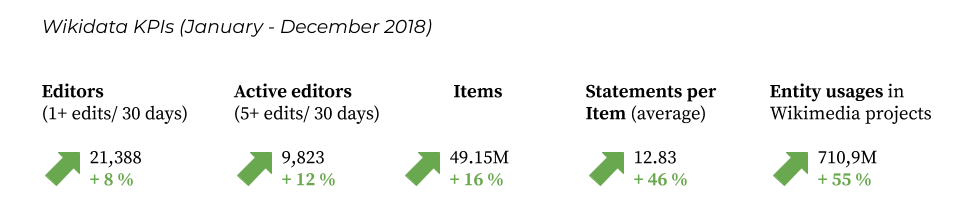

Use of data from Wikidata continues to increase from 326M data uses (as of August 1, 2017) to 386M by the end of 2018. (Baseline end of 2017: 459M) |

Outcome (end of 2018):

710.9M data uses from Wikimedia projects (by 31 December 2018). + 55 % vs. end of 2017 |

Reached |

| Objective:

More editors from the Wikimedia projects additionally edit in Wikidata. We will monitor increase resulting from our work as far as possible. |

Outcome (end of 2018):

No increase in Wikipedia editors who also edit Wikidata: 38.870 (Jan 2018) 36.140 (Apr 2018) 37.110 (Aug 2018) 37.710 (Dez 2018) Work on a client which allows for editing of Wikidata directly in Wikipedia has not been finished yet (expected for Q1 2019). |

Not met |

| Objective:

Entry of at least 5.000 lexemes in Wikidata by the end of 2018. |

Outcome (end of 2018):Since launch of the lexeme entity type in May 40,442 lexemes were created in more than 100 languages (data as of Dec 31, 2018). | Reached |

| Objective:

Data quality in Wikidata improves. This is measured through established quality indicators such as statements per item, percentage of statements with external references, plus additional indicators. |

Outcome (end of 2018):

Data quality indicators are constantly improving. Statements per item: 12.83 (by Nov 30th, plus 4.05 vs. end of 2017) Edits per items: 13.93 (by Nov 30th, plus 0.6 vs. end of 2017) Another indicator for rising trust in the data quality of Wikidata is the increasing usage in other Wikimedia projects. |

Reached |

| Objective:

The independent installation and operation of Wikibase becomes easier. Ten new, publicly accessible websites that are based on Wikibase are enabled by the end of 2018. |

Outcome (end of 2018):

22 public Wikibase installations are listed in the registry by end of 2018, compared to 3 in 2017. Note: This metric underestimates the real number of public Wikibase installations, as not all installations are mapped in the registry. |

Reached |

| Objective:

At least five new success stories publicly showcase the usefulness of Wikidata and Wikibase for third parties. |

Outcome (end of 2018):

Selected success stories: |

Reached |

| Objective:

The average queries to the Wikidata Query Service per quarter rises to 4,5 Million daily (until 31.12.2018). |

Outcome (end of 2018):

Average daily queries to the Wikidata query service: ~4.35 Million (as of Dec 2018). Slightly below the expected target. Potentially due to shifting of some queries of bigger users to own query installations or linked data fragments (which are not covered by this analytic). |

Partly met |

| Objective:

Starting with the prioritized list of technical wishes of the German-speaking Wikipedia community, we have processed at least eight of the most important user problems in MediaWiki. For each of these, this thorough analysis will lead to either a plan for development or a decision to not pursue due to non-feasibility. |

Outcome (by end of 2018):

7 of the most important user problems have been analyzed (full list here). Analysis process was continually improved.

|

Partly met |

| Objective:

At least three user problems have been solved and the solutions are sustainably usable for the highest number of Wikimedia projects possible. |

Outcome (by end of 2018 ):

3 solutions were published broadly:

Full list of shipped standard and beta features here. |

Reached |

| Objective:

The technical innovations are optimally usable for diverse groups of users . By the start of Q1, we will complete a list of criteria to be considered for technical development work in 2018. |

Outcome (by end of 2018):

A list of criteria was set up in Q1, which now informs the development process. |

Reached |

| Objective:

By the end of 2018, our team will publish findings and experiences from collaborative software development. |

Outcome (by end of 2018):Publishing of a white paper which summarizes our findings and experiences from collaborative software development. | Reached |