Europeana/1914-18/Wikimedia Eesti/EN

The First World War could also be described as a forgotten war in Estonia. Since the conquest of Estonia in the Great Northern War at the beginning of 18th century, the Estonian territory had been part of the Russian Empire, and just like with previous wars, Estonians were drafted into military service to fight for the foreign state, but all of that remained somewhat distant. The scale of the war and its proximity had indeed made it more significant, than, for instance, the previous wars with the Turks, or the Russo-Japanese War, but as everything is measured in comparison with something, then we must also look at what followed it, to get the sense of what the war meant for Estonians in the long run.

The power vacuum in the Russian Empire at the end of the war made it possible to seek independence for many nations from within the former Empire. So did the Estonians, and the act of declaring independence inevitably resulted in the Estonian War of Independence with Russia and with Baltische Landeswehr. The war, that was fought with three separate sides, which lasted from 28 November 1918 to 2 February 1920, and which resulted in the independence of a nation that until then had been under foreign rule for 700 years, quickly became defined as the most significant achievement in the history of that nation. Thus were lost the nation's attention to, and self-perception of this Great War; the far-reaching results of which dissolved the great empires in Europe, and guided the course of the ongoing century, and the next.

In the years from 1914 to 1918, around 100,000 Estonians were mobilized. A remarkable number for a nation of a mere one million. And with great losses in the Russian army, many Estonians got the chance of rising in the ranks, that then prepared them for leading their own groups of soldiers in the upcoming war that marked the high point of Estonian history. So did this conflict, that took the lives of 10,000 men, directly merge with the events that followed, and their shadow was mostly subsumed into a draggy training exercise. Yet the same notion, as experienced by Estonians one century ago, can also be shared many other nations of Eastern Europe, whose fate in those years was thoroughly rewritten, and who captured new vigor from their rediscovered existence.

Just like the world order had been turned on its head, and Europe had the task of rebuilding itself, major changes in the cultural sphere took place. The Old was quickly vanishing, and making way for the very New. Advancements in technology and the new social order only hastened the progress. Even in Estonia, it was just a blink of an eye, when the natives, who before were seen as belonging to a lower caste, took leading positions in all of the fields of life. Seemingly coming out from nowhere, the process had begun long before, and it was just the changes in the social order, that helped to catalyze the speed of unfolding events.

But what did the Estonian art scene look like during those years? It was in only 1906, when the first Estonian Art Exhibition opened (retaining its name going forward), that featured Estonian authors. What shape did the Estonian art take by the second decade of the 20th century, when alongside earlier names came a large number of young artists? This later period of the second decade, as presented in this virtual exhibition, shows the very youth of the Estonian art, with the artists looking to develop their own unique styles, and to make a name for themselves.

The outside world was stepping in with its modernist movements in the midst of the chaos, and with the hopes of greater autonomy, the need to define what is Estonian in its essence, grew stronger by the day. The war may have acted as a force of destruction in the West, but within the borders of this small country, it precipitate the spread of knowledge about the external world. Just like the poet Gustav Suits had previously written in relation with the literary group Young Estonia (Noor-Eesti) that was established around 1905: "Let us remain Estonians, but let us become Europeans, too". That way, it's wholly prudent how the formerly agrarian societies in Eastern Europe joined the ranks of modernized countries, and how that cultural shift flowed through them. May this be a glimpse of the defining moments prior to the birth of the Estonian state.

This exhibition is part of Europeana 1914-1918 project and was set together by:

- Ivo Kruusamägi (Wikipedia)

- Merli-Triin Eiskop (Tartu Art Museum)

- Stina Sarapuu (Art Museum of Estonia)

It contains works from the collections of Tartu Art Museum and Art Museum of Estonia.

-

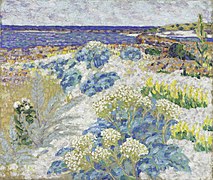

Konrad Mägi. Sea Kales (1913–1914)

-

Herbert Lukk. Haystacks (1914)

-

Nikolai Triik. View from a Window (1914)

-

Nikolai Triik. Portrait of O. Martna (1914)

-

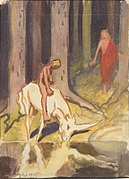

Kristjan Raud. The Witch and Piglets (1914)

-

Oskar Kallis. Making Headstand (1914)

-

Välko Tuul. Portrait of an Old Man (1914)

-

Ants Laikmaa. Landscape with a homestead (Saaremaa Landscape) (1914)

-

Ants Laikmaa. A Tunisian Girl (Bedouin Woman in White) (1914)

-

Ants Laikmaa. Portrait of a Bedouin Woman (1915)

-

Nikolai Triik. View of Tallinn (1915)

-

Erich Kügelgen. Motif (1915)

-

Lilly Walther. A Sitting Female Figure (Portrait of Mrs Bremen) (1915)

-

Lilly Walther. Riverside Landscape (1915)

-

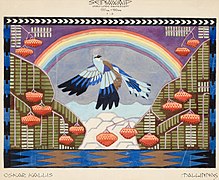

Oskar Kallis. The Siuru Bird from the Estonian National Epic Kalevipoeg. Design for a wall carpet (1915)

-

Välko Tuul. Adam and Eve (1915)

-

Välko Tuul. Viking Ships (1915)

-

Välko Tuul. Man in Chains (1915–1917)

-

Konrad Mägi. Landscape of Estonia (1915–16)

-

Konrad Mägi. On the Road from Viljandi to Tartu (1915–16)

-

Konrad Mägi. Meditation (Landscape with a lady) (1915–1916)

-

Konrad Mägi. Portrait of Ida Menning (1915–1916)

-

Jaan Koort. Portrait of the Artist’s Wife (1916)

-

Oskar Kallis. The Dance of Life (1916)

-

Paul Burman. Still Life (Flowers) (1916)

-

Balder Tomasberg. Heroic Landscape (1916)

-

Johannes Einsild. Otepää landscape (1917)

-

Nikolai Triik. An Old Garden (1917)

-

Nikolai Triik. Portrait of Ella Lüüs (1917)

-

Aleksander Uurits. Portrait of a Lady (1917)

-

Oskar Kallis. Linda Carrying a Rock (1917)

-

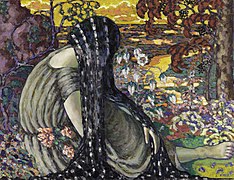

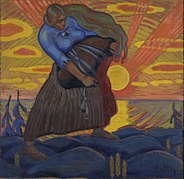

Oskar Kallis. The Kiss of the Sun (1917)

-

Aleksander Uurits. Warriors on Horseback (1917)

-

Aleksander Uurits. Military Hospital (1914–17)

-

Villem Ormisson. Still life with coloured eggs (1914–18)

-

Konrad Mägi. Portrait of a Man (1917–18)

-

Konrad Mägi. Portrait of Ado Vabbe (1918)

-

Herbert Lukk. Self-Portrait (1918)

-

Kuno Veeber. Potato Harvesters (1918)

-

Ants Laikmaa. Taebla-Nõmme (1918)

-

Balder Tomasberg. View of Paldiski (1918)

-

Balder Tomasberg. Nocturno (1918)

-

Balder Tomasberg. Dream (1918)

-

Lilly Walther. View between Jalta and Hursuf (1918)

-

Herbert Lukk. View across Tallinn towards the Harbour (1918)

-

Herbert Lukk. Courtyard (1918)